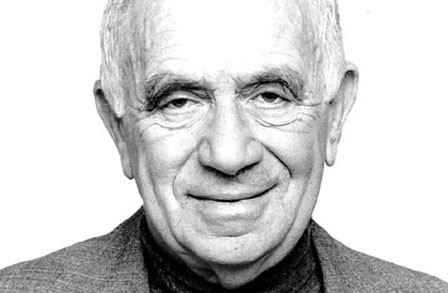

Yehuda Amichai

Current City, State, Country

Birth City, State, Country

Biography

Yehuda Amichai was born in Germany into an Orthodox Jewish family in 1924; they would later flee the country during the rise of Hitler and settled in Palestine when Yehuda was twelve years old. After graduating high school, Yehuda served in the Jewish Brigade of the British army during World War II, and then later fought with the Israeli defense forces during the Arab-Israeli wars. The horrors he witnessed during these conflicts heavily informed his interest in, as well as the subject of his poetry. During an interview with The Paris Review, he argued that all poetry is grounded in politicism in some way, and that “real poems deal with a human response to reality, and politics is part of reality, history in the making. . . even if a poet writes about sitting in a glass house drinking tea, it reflects politics.” During his service in WWII, he began to find interest in poetry, and read authors such as T.S. Eliot and W.H. Auden.

After his time in the military, Amichai attended Hebrew University, where he would later teach. He studied Hebrew texts and literatures, and went on to teach at secondary schools, as well as some American universities. He published his first collection in 1955, titled Akhshav u-ve-yamim aḥerim (“Now and In Other Days”), where he explored Jewish history, and employed biblical imagery to reflect on contemporary society. By the mid-1960s, Amichai was already regarded as one of the world’s leading poets among many circles in Israel. His collection Amen (1977) was able to reach wider audiences with an English translation by Ted Hughes. His subject matter expanded with each collection he released, with poems focused on a variety of phenomena such as war, Jewishness, sexuality, and history. Yehuda Amichai has published numerous volumes of poetry, two novels, short stories, plays, and has had his work translated into nearly forty different languages. In Israel, his books were frequent bestsellers, and he was awarded the Israel Prize for Poetry in 1982 for effecting “a revolutionary change in poetry’s language.” He was also nominated for a Nobel Prize.

Yehuda Amichai has been called “the most widely translated Hebrew poet since King David” and gained notoriety for his complex and allusive use of Hebrew, a language not his own, his first language being German. His mastery of the language and form continues to crystalize his title of one of the best poets of all time, translator Robert Alter celebrates Amichai’s use of “his own language and literary tradition as a delicately tuned instrument that communicates to Hebrew readers certain tonalities that others will not hear.” Even with the complexities of the original Hebrew translated out, his body of work continues to highlight his powers as an everyman, speaking for both his people and for the world. Reviewing The Selected Poetry of Yehuda Amichai, American poet Ed Hirsch stated that Amichai “is a representative man with unusual gifts who in telling his own story also relates the larger story of his people.”

Amichai was married twice and fathered a son to his first wife, Tamar Horn, then a son and daughter to his second wife, Chana Sokolov. He lived in Jerusalem until his death on September 22nd, 2000.

(Biography courtesy of The Poetry Foundation, The American Academy of Poets, Britannica, and The Jerusalem Post)

What is the relationship between Judaism and/or Jewish culture and your poetry?

One of the most detailed accounts of Amichai’s relationship with Judaism comes from his 1989 interview with The Paris Review. When asked about how living in a post-World War I Germany impacted his family, and his community, Amichai first explains the context up his upbringing; “Würzburg

had a very strong Jewish community—two thousand or so, in a town of a hundred thousand inhabitants. But two thousand was quite a substantial Jewish community at that time. There was a Jewish hospital and a Jewish school—a state school Jews could go to. I learned Hebrew in first grade, to read and write Hebrew as well as German, which may explain why I had no trouble with Hebrew later on.” (Amichai 216) He describes his father as “a German Jew, very Orthodox, a strong believer, in the best sense of the word.” (Amichai 215)

Amichai also goes into depth about the struggle many Jews felt in fighting for Germany in World War I, explaining that Jews were “divided among feuding nations. There were Jews fighting for Germany, for France, for Britain, for Russia, Jewish rabbis praying for the Allies, for the Turks, for the Germans and the Austrians.” His father and uncle both fought in WWI, a topic he’s touched on in many of his poems.

Amichai speaks very fondly of his extended family, which consisted entirely of Orthodox Jews, and remarks that “There was a strong, warm, very protected feeling among us.” (Amichai 216) When asked by the interviewer whether he would classify his upbringing as religious, he vehemently agrees, “Very much so. I went to synagogue regularly. My first education was interpreting the Bible. But I also grew up with German folk songs and stories, which became as much a part of my imagination as the Bible stories. My sense of history came from these stories—I was fascinated with what you might call “fairy-tale-shaped history.” But from the beginning, I felt I belonged to a different people, which wasn’t any problem for me.” This sense of difference went on to influence his writing and artistic ideologies in general, “I existed in a realm of dream, in the realm of the romantic, in a romantic dream of moving from a place where we were a small group, sometimes victimized, to a Jewish Palestine which had ancient roots in the Bible.” (Amichai 219)

On his relocation to Palestine from Germany at age 11, and whether that was a difficult adjustment, Amichai says “No, not at all. I moved immediately into a Hebrew speaking culture and society. I had learned Hebrew at school in Germany and had no difficulty speaking and reading it in Palestine. We spoke German at home, but I became fluent in Hebrew.” He clarifies that it wasn’t all easy, as persecution towards Jews rose throughout the world. “We could hear shooting at night—not a lot, but enough to remember it. And the elders of the family—my father, uncles, my older cousins—had to go on guard duty. And we were prohibited from going too far from the village—we couldn’t go to Jaffa, for example, because it was too dangerous. But all this was natural to the way we lived, to our lives. No one was actually afraid; we just had to be careful, and all of us took care of one another.” (Amichai 222)

When fighting in WW2, Yehuda Amichai says that is where his love for literature, and his first thoughts of writing poetry were born. “The British had these mobile libraries for their soldiers, but, of course, most of the British soldiers, being from the lower classes and pretty much uneducated, didn’t make much use of the libraries. It was mostly us Palestinians who used them—there we were, Jews reading English books while the English didn’t. There had been some kind of storm, and one of the mobile libraries had overturned into the sand, ruining or half-ruining most of the books. We came upon it, and I started digging through the books, and came upon a book, a Faber anthology of modern British poetry, which I think came out in the late thirties. . .This book had an enormous impact on me—I think that was when I began to think seriously about writing poetry.”

Further discussing influences on his work, Amichai explains that time is the most important dimension in his writing, explaining that “Time, for me, is imaginatively comparative and continuous; I have an almost physical sense of memory recall. I can pick up any point in my life and be almost physically right there, but in an emotional sense. It’s easy for me to shortcut back to my childhood, my adolescence, my wars. It’s actually a very Jewish sense of time, out of the Talmud. There’s a Talmudic saying that “there’s nothing early or late in the Bible,” which means that everything, all events, are ever present, that the past and future converge on the present, especially in language.” He speaks a lot about his relationship to language—especially Hebrew—and how his background as an Orthodox Jew impacted how he viewed Hebrew. He found himself in an environment where the everyday language was one that had previously been reserved for prayer or religious events. He calls this mixture of religious and common Hebrew “mixed sensibility or imagination of the language” and claimed that it “was my natural way to write poems.” (Amichai 232)

Published Works

Poetry in Translation

Open Closed Open: Poems; translated from the Hebrew by Chana Bloch and Chana Kronfeld (Harcourt, 2000)

Exile at Home; photographs by Frederic Brenner (Harry N. Abrams, 1998)

The Great Tranquility: Questions and Answers; translation from the Hebrew by Abramson and Parfitt (Harper, 1983; reprinted, Sheep Meadow Press, 1997)

I Am Sitting Here Now (Land Marks Press, 1994)

Poems: English and Hebrew (Shoken, Jerusalem, 1994)

Yehuda Amichai: A Life of Poetry, 1948-1994; translated by Barbara and Benjamin Harshav (HarperCollins, 1994)

Poems of Jerusalem; and, Love Poems: Bilingual Edition (Sheep Meadow Press, 1992)

Even a Fist Was Once an Open Palm with Fingers: Recent Poems; selected and translated by Barbara and Benjamin Harshav (HarperCollins, 1991)

The Early Books of Yehuda Amichai; translated by Yehuda Amichai and Ted Hughes (Sheep Meadow Press, 1988)

Poems of Jerusalem: A Bilingual Edition (Harper, 1988)

Travels (bilingual edition); English translations by Nevo (Sheep Meadow Press, 1986)

The Selected Poetry of Yehuda Amichai; translation from the Hebrew by Mitchell and Chana Bloch (Harper, 1986; revised and expanded edition, University of California Press, 1996)

Love Poems; translation from the Hebrew by Glenda Abramson and Tudor Parfitt (Harper, 1981)

On New Year’s Day, Next to a House Being Built (Sceptre Press Knotting, England, 1979)

Time: Poems (Harper, 1979)

Amen; translation from the Hebrew by Yehuda Amichai and Ted Hughes (Harper, 1977)

Travels of a Latter-Day Benjamin of Tudela; translation from the Hebrew by Ruth Nevo (House of Exile; Ontario, Canada, 1976)

Songs of Jerusalem and Myself; translation from the Hebrew by Schimmel (Harper, 1973)

Poems by Yehuda Amichai; introduction by Michael Hamburger (Harper, 1969)

Prose

The World Is a Room, and Other Stories (Jewish Publication Society, 1984)

Lo me-’akhshav, Lo mi-kan (Tel Aviv, Israel, 1963); translation by Shlomo Katz published as Not of This Time, Not of This Place (Harper, 1968)

As Editor

Points of Departure, Dan Pagis; co-editor with Mandelbaum; translation from the Hebrew by Stephen Mitchell (Jewish Publication Society, 1982)

The Syrian-African Rift, and Other Poems, Avoth Yeshurun; co-editor with Allen Mandelbaum; translation by Schimmel (Jewish Publication Society, 1980)

In Hebrew

Me-ahore kol zeh mistater osher gadol; poetry; title means “Behind All This Lies a Great Happiness” (1974)

Mi yitneni malon; title means “Hotel in the Wilderness” (Bitan, 1972)

Ve-lo ‘al menat li-zekor; poetry (Hotsaat Shoken, 1971)

‘Akshav ba-ra’ash (1968)

Mah she-karah le-Roni bi-Nyu York; title means “What Happened to Roni in New York” (1968)

Pa ‘amonim ve-rakavot; radio play; title means “Bells and Trains” (1968)

Shirim, 1948-1962; title means “Poetry” (Jerusalem, 1963)

Masa’ le-Ninveh; play; title means “Journey to Nineveh” (1962)

Be-ruah ha-nora’ah ha-zot; stories; title means “In this Terrible Wind” (Merhavya, 1961)

Ba-ginah ha-tsiburit; poetry; title means “In the Park” (Jerusalem, 1958-59)

Be-merhak shete tikvot; poetry; title means “Two Hopes Apart” (Tel Aviv, Israel, 1958)

Akhshav uva-yamim ha-aherim; poetry; title means “Now and in Other Days” (Tel Aviv, Israel, 1955)

Links to Sample Works

Video Reading

Education

Hebrew University of Jerusalem